Author: Leónidas Neftalí González Campos

Mar 28, 2025

Writing A Shader Reflection System In Vulkan

Note: All code presented here is a simplification of the implementation you can find in HushEngine

Table of Contents

Premise and purpose

When making a game engine you generally want the end-user, the game developer to be able to interact and expand your systems, and rendering is one of the most important ones to get right, as it makes or breaks the style of their game. To enable our user’s creativity, they need to be able to write their own shaders, and the engine should provide them with an easy to use API that will allow them to modify values of their materials at runtime or in the editor, this can make for cool mesh effects and custom post-processing alike.

We don’t have the time or energy to implement our own shading language like Unity did with ShaderLabs (as they include runtime information about the shader in the actual code),

The setup

We’ll be using the HushEngine’s tech stack, which is comprised of:

- C++20

- Vulkan 1.3+

- GLSL version 450

- SPIRV-Reflect All examples below will follow assuming these are the base technologies we’re working with.

Some basic terminology

Graphics is a complex topic, so with the purpose of brevity, I’ll be using some loose terms to refer to more extensive concepts.

- CPU-Land

- Code and regions of memory that can be accessed and modified using general purpose programming languages, hence they are bound to the CPU-side of things.

- GPU-Land

- Code and regions of memory that can ONLY be accessed within shaders, hence they are bound to the GPU-side of things.

Alright, let’s get started!

Shader Modules

To start we’ll need to upload our compiled shaders to Vulkan, we’ll assume you already have a rendering pipeline setup because god knows that’s out of scope for this article.

We’ll create a function to load both vertex and fragment shaders from the filesystem, this operation could fail so we’ll also include some errors as values return codes.

ShaderMaterial.hpp

class ShaderMaterial {

public:

enum class EError

{

None = 0,

FragmentShaderNotFound,

VertexShaderNotFound

};

/// @brief Will create and bind pipelines for both shaders

// Returns an error in case this fails

EError LoadShaders(IRenderer *renderer, const std::filesystem::path &fragmentShaderPath, const std::filesystem::path &vertexShaderPath);

private:

IRenderer *m_renderer;

};We assume IRenderer to be an API-agnostic renderer interface that we can turn into the implementation specific one later on.

SPIRV buffers

HushEngine supports shaders written in any language, as long as they get compiled to the spirv representation, the graphics developer can just pick their language of choice and feed the engine the cross platform compiled binary, this however means that we (at least at the moment) do not support hot reloading, but that is our cross to bear (and a problem for our future selves when we eventually want to include it).

Shaders compiled to the .spv file format can be reflected on with the SPIRV-Reflect library which is the package we’ll be using to get information about the shader’s memory layout and how to build an API around it.

SPIRV-Reflect expects the shader data to be a buffer of unsigned 32-bit separated elements describing the compiled shader (std::vector<uint32_t> spirvByteCodeBuffer).

Let’s make a utility class to help us load in each shader.

VulkanHelper

class VulkanHelper final

{

public:

static bool LoadShaderModule(const std::string_view &filePath, VkDevice device, VkShaderModule *outShaderModule, std::vector<uint32_t> *outBuffer);

private:

static void ReadDataInto(std::vector<uint32_t> &buffer, std::ifstream &file, size_t fileSize);

};

VulkanHelper Implementation

bool Hush::VulkanHelper::LoadShaderModule(const std::string_view &filePath, VkDevice device, VkShaderModule *outShaderModule, std::vector<uint32_t> *outBuffer)

{

// Open the file. With cursor at the end

std::ifstream file(filePath.data(), std::ios::ate | std::ios::binary);

if (file.fail() || !file.is_open())

{

return false;

}

// Find what the size of the file is by looking up the location of the cursor

// Because the cursor is at the end, it gives the size directly in bytes

uint32_t fileSize = static_cast<uint32_t>(file.tellg());

// Create a new shader module, we'll make this reference our loaded buffer

VkShaderModuleCreateInfo createInfo = {};

createInfo.sType = VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_SHADER_MODULE_CREATE_INFO;

createInfo.pNext = nullptr;

// Spirv expects the buffer to be on uint32, so make sure to reserve a int

// vector big enough for the entire file

size_t bufferSize = fileSize / sizeof(uint32_t);

outBuffer->resize(bufferSize, 0);

ReadDataInto(*outBuffer, file, fileSize);

// codeSize has to be in bytes, so multply the ints in the buffer by size of

// int to know the real size of the buffer

createInfo.codeSize = outBuffer->size() * sizeof(uint32_t);

createInfo.pCode = outBuffer->data();

VkShaderModule shaderModule = nullptr;

if (vkCreateShaderModule(device, &createInfo, nullptr, &shaderModule) != VK_SUCCESS)

{

return false;

}

*outShaderModule = shaderModule;

return true;

}

void Hush::VulkanHelper::ReadDataInto(std::vector<uint32_t> &buffer, std::ifstream &file, size_t fileSize)

{

// Put file cursor at beginning

file.seekg(0);

// Load the entire file into the buffer

auto *fileData =

reinterpret_cast<char *>(buffer.data()); // We downsize this, but idk, this is how it expects us to use it

file.read(fileData, fileSize);

// Now that the file is loaded into the buffer, we can close it

file.close();

}

These functions can now be used to properly load both of our shaders into memory back on ShaderMaterial.cpp.

ShaderMaterial.cpp

Hush::ShaderMaterial::EError Hush::ShaderMaterial::LoadShaders(IRenderer *renderer, const std::filesystem::path &fragmentShaderPath, const std::filesystem::path &vertexShaderPath)

{

this->m_renderer = renderer;

auto *rendererImpl = dynamic_cast<VulkanRenderer *>(renderer);

VkDevice device = rendererImpl->GetVulkanDevice();

VkShaderModule meshFragmentShader = nullptr;

std::vector<uint32_t> spirvByteCodeBuffer;

if (!VulkanHelper::LoadShaderModule(fragmentShaderPath.string(), device, &meshFragmentShader, &spirvByteCodeBuffer))

{

return EError::FragmentShaderNotFound;

}

VkShaderModule meshVertexShader = nullptr;

if (!VulkanHelper::LoadShaderModule(vertexShaderPath.string(), device, &meshVertexShader, &spirvByteCodeBuffer))

{

return EError::VertexShaderNotFound;

}

return EError::None;

}We will be constantly modifying this implementation but for now, this just loads in all our shaders so we can run reflection on them.

Speaking of which…

Reflection bindings

A binding is a description of how the shader’s memory is laid out, different GPU memory buffers will have different properties, but we will largely focus on uniform buffers which are specialized structures that group together uniform variables into a single buffer object.

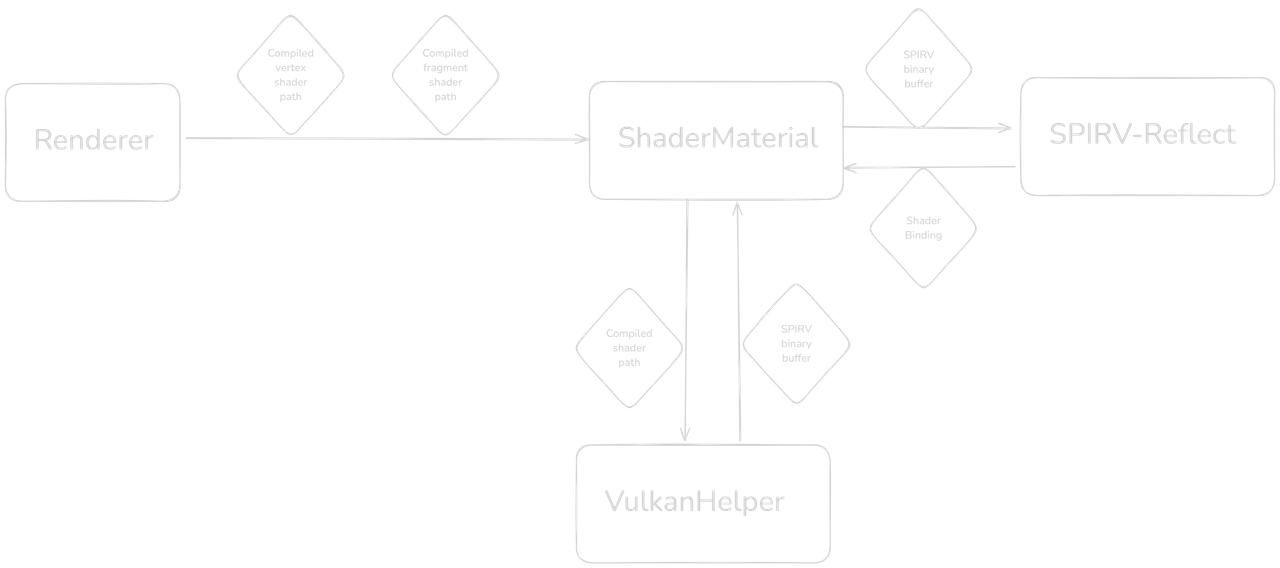

At a high level, the interactions, inputs and outputs of each system should look like this:

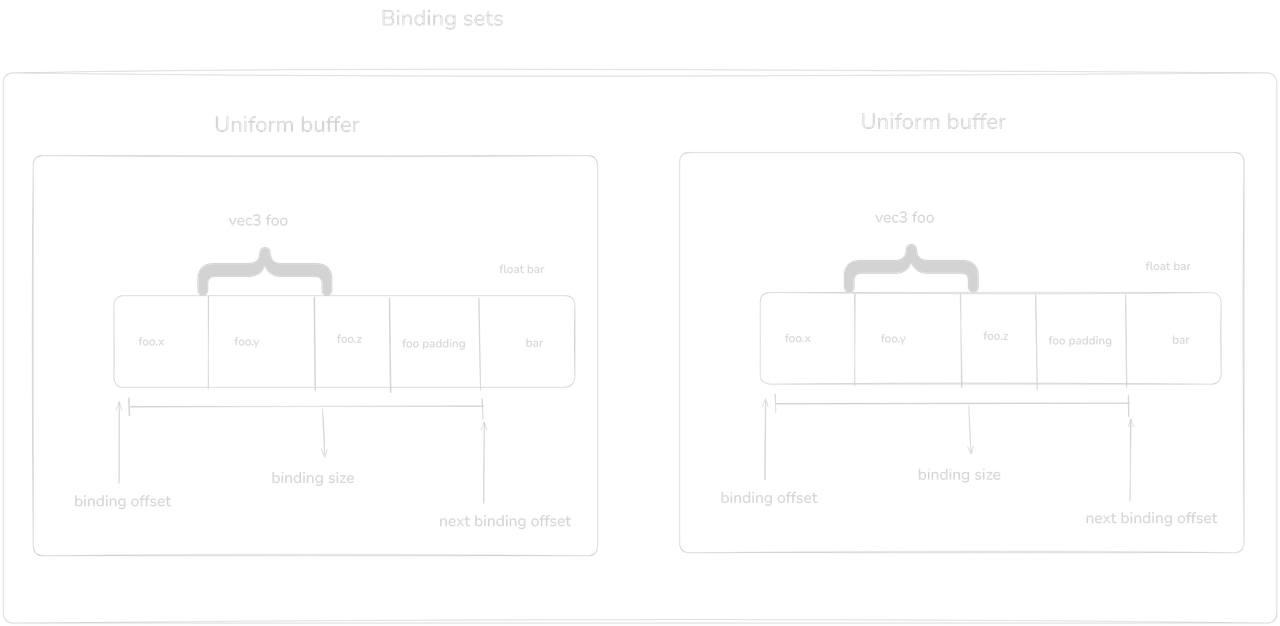

The uniform buffer structure ensures the data members are tightly stored together one after the other with an alignment standard (generally std140, which means the buffer is sectioned into uniformly separated data segments according to these rules:

- Scalars (

bool, int, uint, float)- Aligned to 4 bytes

- Vectors

vec2aligned to 8 bytesvec3aligned to 16 bytesvec4aligned to 16 bytes

Sometimes this will result in extra padding added to the memory layout, for example:

The vec3 data type encapsulates 3 scalar floating point values, of 4 bytes each, which comes down to 12 bytes, but std140 will add an extra 4 bytes to comply with the GPU memory layout, we have to take this into consideration in our binding structure.

ShaderBindings.hpp

struct ShaderBindings

{

enum class EBindingType

{

Unknown, // There are many, maaaaany more bindings in GLSL, but we'll aim to handle uniforms first

UniformBuffer, // Describes the entire buffer structure, as in, the object that contains all the uniform fields

UniformBufferMember, // Specific uniform field

};

// NOTE: Some of these variables are not all needed for all bindings, but will be there for the applicable ones

uint32_t bindingIndex{}; // Index of the entire buffer

uint32_t size{}; // Padded size of the field (16 for vec3, 8 for vec2, etc.)

uint32_t offset{}; // Where to start reading memory from the buffer

uint32_t setIndex{}; // Index of the descriptor set containing this buffer, we'll assume there is only one set, but will leave here as an excercise to the reader

EBindingType type = EBindingType::Unknown;

};

Shader lay out their structures in simple array-like regions of memory, the data’s “hierarchy” goes like this:

- Binding set (groups buffers, constants, input variables, samplers, etc.)

- Uniform buffers (regions with multiple member variables)

- Members (the regions of bytes that represent the underlying data)

- Uniform buffers (regions with multiple member variables)

Now we’re gonna add a couple new functions to our ShaderMaterial to process these bindings.

ShaderMaterial.hpp

private:

Result<std::vector<ShaderBindings>, EError> ReflectShader(const std::span<std::uint32_t>& shaderBinary);

// Will bind Vulkan layouts to the shader information

EError BindShader(const std::vector<ShaderBindings> &vertBindings, const std::vector<ShaderBindings> &fragBindings);The header file is renderer-agnostic, but we will need to keep references to pipelines and descriptor layouts, so we’re gonna cheat a bit here by having an Opaque structure where all that data will live, it’s somewhat of an ugly approach, but it works well…

OpaqueMaterialData *m_materialData;

// We'll also need a way to access any saved binding by its name, we'll go with a hash map for that

std::unordered_map<std::string, ShaderBindings> m_bindingsByName;

// Lastly we need to know the total padded size of our uniform buffer, we'll create a pointer that maps this memory later

size_t m_uniformBufferSize;

...

};In the implementation file we can define our OpaqueMaterialData structure

ShaderMaterial.cpp

struct OpaqueMaterialData

{

VkMaterialPipeline pipeline{};

VkDescriptorSetLayout descriptorLayout{};

DescriptorWriter writer;

VkBufferCreateInfo uniformBufferCreateInfo{};

};(For anyone potentially confused about the OpaqueMaterialData structure, this is a technique called the Opaque Pointer Pattern.)

Now we’re ready to start getting the shader’s metadata using SPIRV-Reflect, we could technically get an invalid compiled binary as a parameter, so in the interest of proper validation we’ll add some values to our EError enumerator.

ShaderMaterial.hpp

enum class EError

{

None = 0,

FragmentShaderNotFound,

VertexShaderNotFound,

ReflectionError, // Something funky happened when reading the spirv binary

PipelineLayoutCreationFailed, // The pipeline was not able to be created

}ShaderMaterial.cpp

Hush::Result<std::vector<Hush::ShaderBindings>, Hush::ShaderMaterial::EError> Hush::ShaderMaterial::ReflectShader(const std::span<uint32_t>& shaderBinary)

{

size_t byteCodeLength = shaderBinary.size() * sizeof(uint32_t);

SpvReflectShaderModule reflectionModule;

SpvReflectResult rc = spvReflectCreateShaderModule(byteCodeLength, shaderBinary.data(), &reflectionModule);

if (rc != SpvReflectResult::SPV_REFLECT_RESULT_SUCCESS)

{

LogFormat(ELogLevel::Error, "Failed to perform reflection on shader, error: {}", magic_enum::enum_name(rc));

return EError::ReflectionError;

}

// Result that will contain all found bindings

std::vector<ShaderBindings> bindings;

We need to reserve a vector large enough to fit all our descriptors (which will contain all the variables in a uniform buffer), so we query the reflection library twice with spvReflectEnumerateDescriptorBindings, once to get the descriptor count, and a second time to fill up a vector with their data.

uint32_t descriptorCount{};

// First query, we pass nullptr at the end because we don't have an initialized vector yet

spvReflectEnumerateDescriptorBindings(&reflectionModule, &descriptorCount, nullptr);

bindings.reserve(descriptorCount);

std::vector<SpvReflectDescriptorBinding *> descriptorBindings(descriptorCount);

// Now let's actually fill the vector up

spvReflectEnumerateDescriptorBindings(&reflectionModule, &descriptorCount, descriptorBindings.data());

for (const SpvReflectDescriptorBinding *descriptor : descriptorBindings)

{

ShaderBindings binding;

binding.bindingIndex = descriptor->binding;

binding.size = descriptor->block.size;

binding.offset = descriptor->block.offset;

binding.stageFlags = 0;

switch (descriptor->descriptor_type)

{

case SPV_REFLECT_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER:

binding.type = ShaderBindings::EBindingType::UniformBuffer;

this->m_uniformBufferSize += binding.size;

break;

}

bindings.emplace_back(binding);

// Add it to the hash map

this->m_bindingsByName.insert_or_assign(descriptor->name, binding);

// The uniform buffer contains member descriptors, so we skip that processing

if (descriptor->descriptor_type != SPV_REFLECT_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER)

{

continue;

}At this point we’ll iterate through all the members of the found descriptor block, and add those to the bindings map.

// Now, for each member, add it if applicable

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < descriptor->block.member_count; ++i)

{

const SpvReflectBlockVariable &member = descriptor->block.members[i];

// Create a new ShaderBindings entry for each member

Hush::ShaderBindings memberBinding{};

memberBinding.bindingIndex = descriptor->binding; // Same binding index as the block

memberBinding.setIndex = descriptor->set;

memberBinding.size = member.padded_size;

memberBinding.offset = member.offset; // Offset within the uniform block

memberBinding.type = ShaderBindings::EBindingType::UniformBufferMember; // Add a type for UBO members

memberBinding.stageFlags = descriptor->spirv_id;

bindings.emplace_back(memberBinding);

this->m_bindingsByName.insert_or_assign(member.name, memberBinding);

}

}

}With this we’re ready to expose a simple API to read/write to the desired uniform structure.

Memory binding

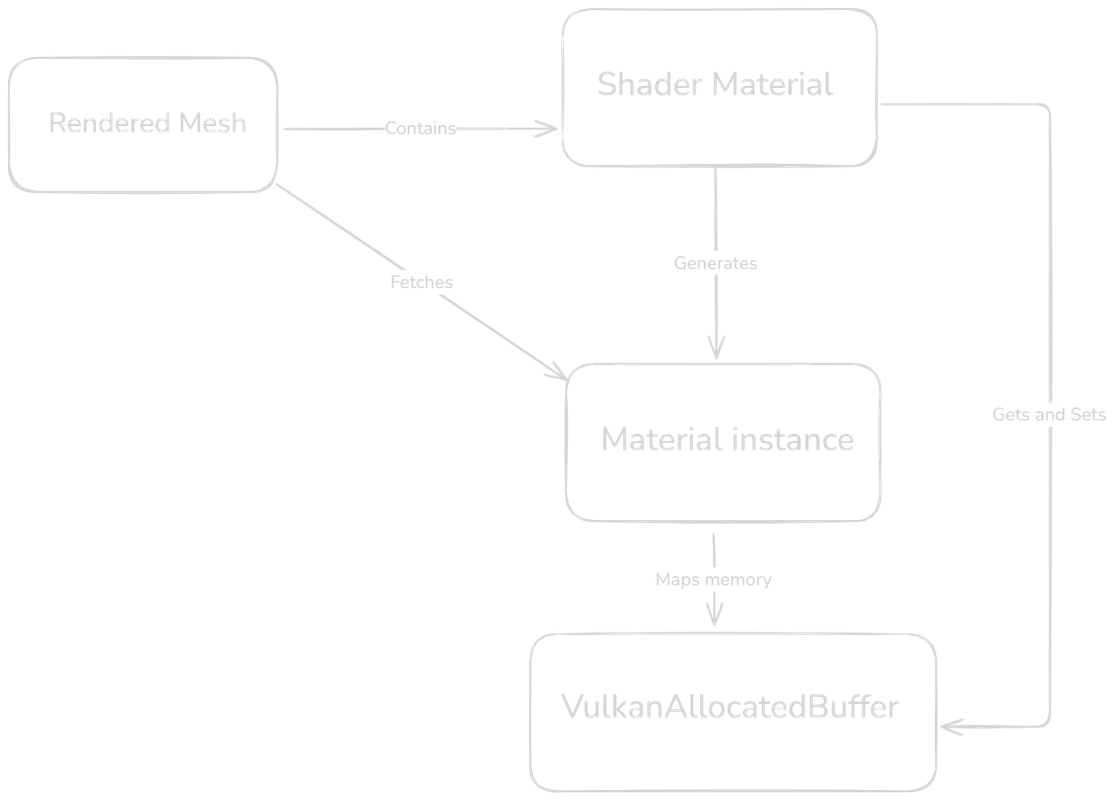

At the end of the day, the purpose of a reflection system like this is to be able to share memory that is modified in CPU-Land and see that change reflected in the material instances of our shaders.

Let’s add one last field to our ShaderMaterial class to control this memory mapping.

ShaderMaterial.hpp

private:

void *m_uniformBufferMappedData = nullptr;Vulkan’s Memory Allocator utility library (VMA) has a few different ways of designating a region of memory that will automatically update its value on GPU-Land although these multiple approaches can be found here we will be using the VMA_ALLOCATION_CREATE_MAPPED_BIT flag when creating the GPU allocated buffer, we have a thin abstraction on this:

VulkanAllocatedBuffer.hpp

class VulkanAllocatedBuffer final

{

public:

VulkanAllocatedBuffer(uint32_t size, VkBufferUsageFlags usage, VmaMemoryUsage memoryUsage,

VmaAllocator allocator);

void Dispose(VmaAllocator allocator) const;

[[nodiscard]]

uint32_t GetSize() const noexcept;

[[nodiscard]]

VmaAllocation GetAllocation();

[[nodiscard]]

VkBuffer GetBuffer();

[[nodiscard]]

VmaAllocationInfo &GetAllocationInfo() noexcept;

private:

VkBuffer m_buffer = nullptr;

VmaAllocation m_allocation = nullptr;

VmaAllocationInfo m_allocInfo{};

/// @brief The size of the current data in the buffer, must be <= m_capacity

uint32_t m_size = 0;

/// @brief The initial size of the buffer's data, and therefore, the max size it accepts

uint32_t m_capacity = 0;

VmaAllocator m_allocatorRef;

};

We will obviate the getters, the important functions are it’s constructor and the Dispose method

VulkanAllocatedBuffer.cpp

Hush::VulkanAllocatedBuffer::VulkanAllocatedBuffer(uint32_t size, VkBufferUsageFlags usage, VmaMemoryUsage memoryUsage,

VmaAllocator allocator)

{

VkBufferCreateInfo bufferInfo = {};

this->m_size = size;

this->m_capacity = size;

bufferInfo.sType = VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_BUFFER_CREATE_INFO;

bufferInfo.pNext = nullptr;

bufferInfo.size = size;

bufferInfo.usage = usage;

VmaAllocationCreateInfo vmaallocInfo = {};

vmaallocInfo.usage = memoryUsage;

// Use the mapped bit to keep the memory linked between CPU and GPU

vmaallocInfo.flags = VMA_ALLOCATION_CREATE_MAPPED_BIT;

// Allocate the buffer

HUSH_VK_ASSERT(vmaCreateBuffer(allocator, &bufferInfo, &vmaallocInfo, &this->m_buffer, &this->m_allocation, &this->m_allocInfo), "Buffer allocation failed!");

this->m_allocatorRef = allocator;

}

void Hush::VulkanAllocatedBuffer::Dispose(VmaAllocator allocator) const

{

vmaDestroyBuffer(allocator, this->m_buffer, this->m_allocation);

}We will rewrite the LoadShaders function to add everything we’ve done so far…

NOTE: THE FUNCTION USES A PIPELINE BUILDER UTILITY, PIPELINES ARE OUT OF THE SCOPE OF THIS ARTICLE, SO WE OBVIATE THAT PROCESS AS WELL, VISIT THE VULKAN GUIDE FOR A BASIC IMPLEMENTATION

ShaderMaterial.cpp

Hush::ShaderMaterial::EError Hush::ShaderMaterial::LoadShaders(IRenderer *renderer, const std::filesystem::path &fragmentShaderPath, const std::filesystem::path &vertexShaderPath)

{

this->m_renderer = renderer;

auto *rendererImpl = dynamic_cast<VulkanRenderer *>(renderer);

VkDevice device = rendererImpl->GetVulkanDevice();

this->m_materialData = new OpaqueMaterialData();

this->InitializeMaterialDataMembers();

VkShaderModule meshFragmentShader = nullptr;

std::vector<uint32_t> spirvByteCodeBuffer;

if (!VulkanHelper::LoadShaderModule(fragmentShaderPath.string(), device, &meshFragmentShader, &spirvByteCodeBuffer))

{

return EError::FragmentShaderNotFound;

}

// Reflect on fragment shader

std::span<uint32_t> byteCodeSpan(spirvByteCodeBuffer.begin(), spirvByteCodeBuffer.end());

Result<std::vector<ShaderBindings>, EError> fragBindingsResult = this->ReflectShader(byteCodeSpan);

VkShaderModule meshVertexShader = nullptr;

if (!VulkanHelper::LoadShaderModule(vertexShaderPath.string(), device, &meshVertexShader, &spirvByteCodeBuffer))

{

return EError::VertexShaderNotFound;

}

// Reflect on vertex shader (using the same buffer to avoid more allocations)

byteCodeSpan = std::span<uint32_t>(spirvByteCodeBuffer.begin(), spirvByteCodeBuffer.end());

Result<std::vector<ShaderBindings>, EError> vertBindingsResult = this->ReflectShader(byteCodeSpan);

this->BindShader(vertBindingsResult.value(), fragBindingsResult.value());

// build the stage-create-info for both vertex and fragment stages. This lets

// the pipeline know the shader modules per stage

VulkanPipelineBuilder pipelineBuilder(this->m_materialData->pipeline.layout);

pipelineBuilder.SetShaders(meshVertexShader, meshFragmentShader);

pipelineBuilder.SetInputTopology(VK_PRIMITIVE_TOPOLOGY_TRIANGLE_LIST);

pipelineBuilder.SetPolygonMode(VK_POLYGON_MODE_FILL);

// TODO: Make cull mode dynamic depending on the reflected shader code / inspector

pipelineBuilder.SetCullMode(static_cast<VkCullModeFlags>(this->m_cullMode), VK_FRONT_FACE_CLOCKWISE);

pipelineBuilder.SetMultiSamplingNone();

pipelineBuilder.SetAlphaBlendMode(this->m_alphaBlendMode);

pipelineBuilder.DisableDepthTest();

// render format

pipelineBuilder.SetColorAttachmentFormat(rendererImpl->GetDrawImage().imageFormat);

pipelineBuilder.SetDepthFormat(rendererImpl->GetDepthImage().imageFormat);

// finally build the pipeline

this->m_materialData->pipeline.pipeline = pipelineBuilder.Build(device);

// clean structures

vkDestroyShaderModule(device, meshFragmentShader, nullptr);

vkDestroyShaderModule(device, meshVertexShader, nullptr);

return EError::None;

}Now finally, we’ll generate the material instance with a rendering API-specific data allocation

ShaderMaterial.cpp

void Hush::ShaderMaterial::GenerateMaterialInstance(OpaqueDescriptorAllocator *descriptorAllocator)

{

auto *rendererImpl = dynamic_cast<VulkanRenderer *>(this->m_renderer);

VkDevice device = rendererImpl->GetVulkanDevice();

this->m_internalMaterial = std::make_unique<GraphicsApiMaterialInstance>();

this->m_internalMaterial->passType = EMaterialPass::MainColor;

// Make sure that we can cast this stuff

auto *realDescriptorAllocator = reinterpret_cast<DescriptorAllocatorGrowable *>(descriptorAllocator);

// Not initialized material layout here from VkLoader

this->m_internalMaterial->materialSet =

realDescriptorAllocator->Allocate(device, this->m_materialData->descriptorLayout);

VulkanAllocatedBuffer buffer(static_cast<uint32_t>(this->m_uniformBufferSize), VK_BUFFER_USAGE_UNIFORM_BUFFER_BIT,

VMA_MEMORY_USAGE_CPU_TO_GPU, rendererImpl->GetVmaAllocator());

// Store our mapped data

this->m_uniformBufferMappedData = buffer.GetAllocationInfo().pMappedData;

// Zero out the data

memset(this->m_uniformBufferMappedData, 0, this->m_uniformBufferSize);

this->m_materialData->writer.Clear();

constexpr size_t offset = 0;

this->m_materialData->writer.WriteBuffer(0, buffer.GetBuffer(), this->m_uniformBufferSize, offset,

VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER);

this->m_materialData->writer.UpdateSet(device, this->m_internalMaterial->materialSet);

}

Setting shader properties

Now that we have a mapped region of memory in the CPU and GPU, we can confidently modify that pointer’s content to set shader data at runtime.

ShaderMaterial.hpp

public:

template <class T>

inline Result<T, EError> GetProperty(const std::string_view &name)

{

HUSH_COND_FAIL_V(this->m_bindingsByName.find(name.data()) != this->m_bindingsByName.end(),

EError::PropertyNotFound);

// Search for a binding with the name passed onto the func

const ShaderBindings &binding = this->FindBinding(name);

if (this->m_uniformBufferMappedData == nullptr)

{

return EError::ShaderNotLoaded;

}

std::byte *dataStartingPoint = static_cast<std::byte *>(this->m_uniformBufferMappedData) + binding.offset;

// Important to reinterpret cast using T, because some stuff might be 16byte-aligned and we want to only get

// the bytes That correspond to the actual value type

return *reinterpret_cast<T *>(dataStartingPoint);

}

template <class T>

inline EError SetProperty(const std::string_view &name, T value)

{

// Search for a binding with the name passed onto the func

constexpr size_t valueSize = sizeof(T);

const ShaderBindings &binding = this->FindBinding(name);

if (this->m_bindingsByName.find(name.data()) == this->m_bindingsByName.end())

{

return EError::PropertyNotFound;

}

HUSH_ASSERT(this->m_uniformBufferMappedData != nullptr,

"Material buffer is not initialized! Forgot to call LoadShaders?");

// Offset the pointer by the binding's offset

std::byte *dataStartingPoint = static_cast<std::byte *>(this->m_uniformBufferMappedData) + binding.offset;

// Memcpy the data with sizeof(T)

memcpy(dataStartingPoint, &value, valueSize);

this->SyncronizeMemory();

return EError::None;

}

Usage

(Oh my god, you made it this far, congrats)

Once you have your mesh created, which is of course, implementation-specific you should be able to bind the material instance and modify its properties in a completely dynamic manner.

VulkanRenderer.cpp

std::filesystem::path frag(R"(C:\Hush-Engine\res\shader.frag.spv)");

std::filesystem::path vert(R"(C:\Hush-Engine\res\shader.vert.spv)");

auto material = std::make_shared<ShaderMaterial>();

ShaderMaterial::EError err = material->LoadShaders(this, frag, vert);

// You will need to have a previously existing global descriptor allocator available here

material->GenerateMaterialInstance(&this->m_globalDescriptorAllocator);

HUSH_ASSERT(err == ShaderMaterial::EError::None, "Failed to load shader material: {}", magic_enum::enum_name(err));

// Setting properties and sending those to a mesh instance

ShaderMaterial::EError resultCode = ShaderMaterial::EError::None;

resultCode = material->SetProperty("pos", cameraPos); // Sending a Vec3

HUSH_ASSERT(resultCode == ShaderMaterial::EError::None, "{}", magic_enum::enum_name(resultCode));

resultCode = material->SetProperty("viewproj", proj * view);

HUSH_ASSERT(resultCode == ShaderMaterial::EError::None, "{}", magic_enum::enum_name(resultCode)); // Sending a mat4

this->m_meshInstance.RecordCommands(cmd, globalDescriptor);Conclusion

If you’ve gotten to the end of this, I mean it, congratulations, Vulkan is not famous for being easy to work with, but hopefully this article at least gave you some fun and interesting ideas to implement on your project, we decided to write this because there were no resources I could find about this topic, and I think it’s valuable information for the graphics developers of tomorrow!